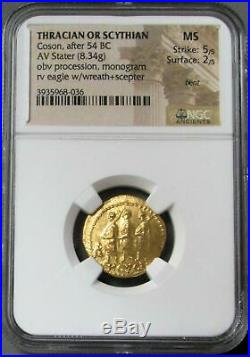

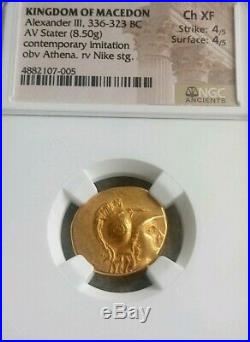

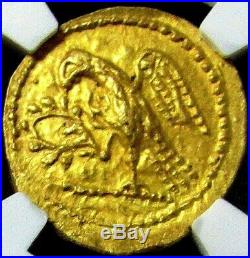

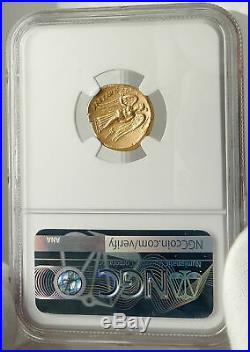

Authentic Ancient Coin of. Assassin of Julius Caesar. Gold Propaganda Coin with Obverse of his silver Coin from 54 B. With his famous ancestor L. Brutus Struck under: Dynast of Thrace: Koson Gold Stater 20mm (8.40 grams) Struck After 44 B. Reference: RPC 1701; BMC Thrace pg. 208, 2; BMCRR II pg. 474, 48 Certification: NGC Ancients. Ch MS Strike: 5/5 Surface: 5/5 3927929-046 KO, Roman consul accompanied by two lictors; BR monogram to left Eagle standing left on sceptre, holding wreath. Koson: Golden Ally of Brutus. Marcus Junius Brutus and C. Cassius Longinus left for Greece in August of 44 BC, having failed to win popular support at Rome following the assassination of Caesar. In the next two years the tyrannicides collected an immense war chest as they assembled their forces for the contest against Antony and Octavian. The historian Appian Bell. 75 tells us that L. Brutus struck from the treasures consigned to him by Polemocratia, the widow of the Thracian dynast Sadalas. Although the identity of the “Koson” named on the coins remains uncertain, the coinage in his name must be the coinage of L. Brutus described by Appian. The obverse depicts the great consul L. Junius Brutus, who expelled the Tarquins from Rome in 509 BC, accompanied by two lictors bearing axes. The design is copied from the denarius issued by M. Junius Brutus when he was a moneyer in 54 BC (Crawford 433/1). The reverse, an eagle standing on a sceptre and holding a victory wreath, was evidently a standard type at Rome and occurs on the coinage of Q. Pomponius Rufus (Crawford 398/1). The monogram is to be read as BR or LBR Brutus or L. The designs express Brutus’ propaganda in the civil war perfectly: the obverse represents the historic fight against tyranny, and the reverse represents the victorious Roman eagle. Lucius Junius Brutus was the founder of the Roman Republic and traditionally one of the first consuls in 509 BC. He was claimed as an ancestor of the Roman gens Junia, including Decimus Junius Brutus and Marcus Junius Brutus, the most famous of Julius Caesar’s assassins. Prior to the establishment of the Roman Republic, Rome had been ruled by kings. Brutus led the revolt that overthrew the last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, after the rape of the noblewoman (and kinswoman of Brutus) Lucretia at the hands of Tarquin’s son Sextus Tarquinius. The account is from Livy’s Ab urbe condita and deals with a point in the history of Rome prior to reliable historical records (virtually all prior records were destroyed by the Gauls when they sacked Rome under Brennus in 390 BC or 387 BC). Overthrow of the MonarchyLucius Iunius Brutus, on right. Main article: Overthrow of the Roman monarchy. Brutus was the son of Tarquinia, daughter of Rome’s fifth king Lucius Tarquinius Priscus and sister to Rome’s seventh king Tarquinius Superbus. According to Livy, Brutus had a number of grievances against his uncle the king, amongst them was the fact that Tarquin had put to death a number of the chief men of Rome, including Brutus’ brother. Brutus avoided the distrust of Tarquin’s family by feigning slow-wittedness (in Latin brutus translates to dullard). He accompanied Tarquin’s sons on a trip to the Oracle of Delphi. The sons asked the oracle who would be the next ruler of Rome. The Oracle responded the next person to kiss his mother would become king. Brutus interpreted “mother” to mean the Earth, so he pretended to trip and kissed the ground. Brutus, along with Spurius Lucretius Tricipitinus, Publius Valerius Publicola, and Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus were summoned by Lucretia to Collatia after she had been raped by Sextus Tarquinius, the son of the king Tarquinius Superbus. Lucretia, believing that the rape dishonored her and her family, committed suicide by stabbing herself with a dagger after telling of what had befallen her. According to legend, Brutus grabbed the dagger from Lucretia’s breast after her death and immediately shouted for the overthrow of the Tarquins. The four men gathered the youth of Collatia, then went to Rome where Brutus, being at that time Tribunus Celerum , summoned the people to the forum and exhorted them to rise up against the king. The people voted for the deposition of the king, and the banishment of the royal family. Brutus, leaving Lucretius in command of the city, proceeded with armed men to the Roman army then camped at Ardea. The king, who had been with the army, heard of developments at Rome, and left the camp for the city before Brutus’ arrival. The army received Brutus as a hero, and the king’s sons were expelled from the camp. Tarquinius Superbus, meanwhile, was refused entry at Rome, and fled with his family into exile. The Oath of Brutus. According to Livy, Brutus’ first act after the expulsion of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus was to bring the people to swear an oath never to allow any man again to be king in Rome. Omnium primum avidum novae libertatis populum, ne postmodum flecti precibus aut donis regiis posset, iure iurando adegit neminem Romae passuros regnare. First of all, by swearing an oath that they would suffer no man to rule Rome, it forced the people, desirous of a new liberty, not to be thereafter swayed by the entreaties or bribes of kings. This is, fundamentally, a restatement of the’private oath’ sworn by the conspirators to overthrow the monarchy. Castissimum ante regiam iniuriam sanguinem iuro, vosque, di, testes facio me L. Tarquinium Superbum cum scelerata coniuge et omni liberorum stirpe ferro igni quacumque dehinc vi possim exsecuturum, nec illos nec alium quemquam regnare Romae passurum. There is no scholarly agreement that the oath took place; it is reported, although differently, by Plutarch (Poplicola , 2) and Appian B. Brutus and Lucretia’s bereaved husband, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, were elected as the first consuls of Rome (509 BC). However, Tarquinius was soon replaced by Publius Valerius Publicola. Brutus’ first acts during his consulship, according to Livy, included administering an oath to the people of Rome to never again accept a king in Rome (see above) and replenishing the number of senators to 300 from the principal men of the equites. During his consulship the royal family made an attempt to regain the throne, firstly by their ambassadors seeking to subvert a number of the leading Roman citizens in the Tarquinian conspiracy. Amongst the conspirators were two brothers of Brutus’ wife Vitellia, and Brutus’ two sons, Titus Junius Brutus and Tiberius Junius Brutus. The conspiracy was discovered and the consuls determined to punish the conspirators with death. Brutus gained respect for his stoicism in watching the execution of his own sons, even though he showed emotion during the punishment. Tarquin again sought to retake the throne soon after at the Battle of Silva Arsia, leading the forces of Tarquinii and Veii against the Roman army. Valerius led the infantry, and Brutus led the cavalry. Aruns, the king’s son, led the Etruscan cavalry. The cavalry first joined battle and Aruns, having spied from afar the lictors, and thereby recognizing the presence of a consul, soon saw that Brutus was in command of the cavalry. The two men, who were cousins, charged each other, and speared each other to death. The infantry also soon joined the battle, the result being in doubt for some time. The right wing of each army was victorious, the army of Tarquinii forcing back the Romans, and the Veientes being routed. However the Etruscan forces eventually fled the field, the Romans claiming the victory. The surviving consul, Valerius, after celebrating a triumph for the victory, held a funeral for Brutus with much magnificence. The Roman noblewomen mourned him for one year, for his vengeance of Lucretia’s violation. Brutus in literature and art. The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons by David, 1789. Lucius Junius Brutus is quite prominent in English literature, and he was quite popular among British and American Whigs. A reference to L. Brutus is in the following lines from Shakespeare’s play The Tragedie of Julius Cæsar , (Cassius to Marcus Brutus, Act 1, Scene 2). O, you and I have heard our fathers say, There was a Brutus once that would have brooktTh’eternal devil to keep his state in RomeAs easily as a king. One of the main charges of the senatorial faction that plotted against Julius Caesar after he had the Roman Senate declare him dictator for life, was that he was attempting to make himself a king, and a co-conspirator Cassius, enticed Brutus’ direct descendant, Marcus Junius Brutus, to join the conspiracy by referring to his ancestor. Brutus is a leading character in Shakespeare’s Rape of Lucrece and in Nathaniel Lee’s Restoration tragedy (1680), Lucius Junius Brutus; Father of his Country. In The Mikado , Nanki-poo refers to his father as “the Lucius Junius Brutus of his race”. The memory of L. Brutus also had a profound impact on Italian patriots, including those who established the ill-fated Roman Republic in February 1849. Brutus was a hero of republicanism during the Enlightenment and Neoclassical periods. In 1789, at the dawn of the French Revolution, master painter Jacques-Louis David publicly exhibited his politically charged masterwork, The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons , to great controversy. Marcus Junius Brutus (early June, 85 BC – late October, 42 BC), often referred to as Brutus , was a politician of the late Roman Republic. He is best known in modern times for taking a leading role in the assassination of Julius Caesar. Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger was the son of Marcus Junius Brutus the Elder and Servilia Caepionis. His father was killed by Pompey the Great in dubious circumstances after he had taken part in the rebellion of Lepidus; his mother was the half-sister of Cato the Younger, and later Julius Caesar’s mistress. Some sources refer to the possibility of Caesar being his real father, despite Caesar’s being only 15 years old when Brutus was born. Brutus’ uncle, Quintus Servilius Caepio, adopted him in about 59 BC, and Brutus was known officially for a time as Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus before he reverted to using his birth-name. Following Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC, Brutus revived his adoptive name in order to illustrate his links to another famous tyrannicide, Gaius Servilius Ahala, from whom he was descended. Brutus held his uncle in high regard and his political career started when he became an assistant to Cato, during his governorship of Cyprus. From his first appearance in the Senate, Brutus aligned with the Optimates (the conservative faction) against the First Triumvirate of Marcus Licinius Crassus, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Gaius Julius Caesar. When civil war broke out in 49 BC between Pompey and Caesar, Brutus followed his old enemy and present leader of the Optimates, Pompey. When the Battle of Pharsalus began, Caesar ordered his officers to take Brutus prisoner if he gave himself up voluntarily, and if he persisted in fighting against capture, to let him alone and do him no violence. After the disaster of the Battle of Pharsalus, Brutus wrote to Caesar with apologies and Caesar immediately forgave him. Caesar then accepted him into his inner circle and made him governor of Gaul when he left for Africa in pursuit of Cato and Metellus Scipio. In 45 BC, Caesar nominated Brutus to serve as urban praetor for the following year. Also, in June 45 BC, Brutus divorced his wife and married his first cousin, Porcia Catonis, Cato’s daughter. According to Cicero the marriage caused a semi-scandal as Brutus failed to state a valid reason for his divorce from Claudia other than he wished to marry Porcia. The marriage also caused a rift between Brutus and his mother, who resented the affection Brutus had for Porcia. Assassination of Julius Caesar (44 BC). Main article: Assassination of Julius Caesar. Death of Caesar by Vincenzo Camuccini. Around this time, many senators began to fear Caesar’s growing power following his appointment as dictator for life. Brutus was persuaded into joining the conspiracy against Caesar by the other senators. Eventually, Brutus decided to move against Caesar after Caesar’s king-like behavior prompted him to. His wife was the only woman privy to the plot. The conspirators planned to carry out their plot on the Ides of March (March 15) that same year. On that day, Caesar was delayed going to the Senate because his wife, Calpurnia Pisonis, tried to convince him not to go. The conspirators feared the plot had been found out. Brutus persisted, however, waiting for Caesar at the Senate, and allegedly still chose to remain even when a messenger brought him news that would otherwise have caused him to leave. When Caesar finally did come to the Senate, they attacked him. Publius Servilius Casca Longus was allegedly the first to attack Caesar with a blow to the shoulder, which Caesar blocked. However, upon seeing Brutus was with the conspirators, he covered his face with his toga and resigned himself to his fate. The conspirators attacked in such numbers that they even wounded one another. Brutus is said to have been wounded in the hand and in the legs. After the assassination, the Senate passed an amnesty on the assassins. This amnesty was proposed by Caesar’s friend and co-consul Marcus Antonius. Nonetheless, uproar among the population caused Brutus and the conspirators to leave Rome. Brutus settled in Crete from 44 to 42 BC. In 43 BC, after Octavian received his consulship from the Roman Senate, one of his first actions was to have the people that had assassinated Julius Caesar declared murderers and enemies of the state. Marcus Tullius Cicero, angry at Octavian, wrote a letter to Brutus explaining that the forces of Octavian and Marcus Antonius were divided. Antonius had laid siege to the province of Gaul, where he wanted a governorship. In response to this siege, Octavian rallied his troops and fought a series of battles in which Antonius was defeated. Battle of Philippi (42 BC). Upon hearing that neither Antonius nor Octavian had an army big enough to defend Rome, Brutus rallied his troops, which totaled about 17 legions. When Octavian heard that Brutus was on his way to Rome, he made peace with Antonius. Their armies, which together totaled about 19 legions, marched to meet Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. The two sides met in two engagements known as the Battle of Philippi. The first was fought on October 3, 42 BC, in which Brutus defeated Octavian’s forces, although Cassius was defeated by Antonius’ forces. The second engagement was fought on October 23, 42 BC and ended in Brutus’ defeat. After the defeat, he fled into the nearby hills with only about four legions. Knowing his army had been defeated and that he would be captured, Brutus committed suicide. Among his last words were, according to Plutarch, By all means must we fly; not with our feet, however, but with our hands. Brutus also uttered the well-known verse calling down a curse upon Antonius (Plutarch repeats this from the memoirs of Publius Volumnius): Forget not, Zeus, the author of these crimes (in the Dryden translation this passage is given as Punish, great Jove, the author of these ills). Plutarch wrote that, according to Volumnius, Brutus repeated two verses, but Volumnius was only able to recall the one quoted. Antonius, as a show of great respect, ordered Brutus’ body to be wrapped in Antonius’ most expensive purple mantle (this was later stolen and Antonius had the thief executed). Brutus was cremated, and his ashes were sent to his mother, Servilia Caepionis. His wife Porcia was reported to have committed suicide upon hearing of her husband’s death, although, according to Plutarch (Brutus 53 para 2), there is some dispute as to whether this is the case: Plutarch states that there is a letter in existence that was allegedly written by Brutus mourning the manner of her death. 85 BC: Brutus was born in Rome to Marcus Junius Brutus The Elder and Servilia Caepionis. 58 BC: He was made assistant to Cato, governor of Cyprus which helped him start his political career. 53 BC: He was given the quaestorship in Cilicia. 49 BC: Brutus followed Pompey to Greece during the civil war against Caesar. 48 BC: Brutus was pardoned by Caesar. 46 BC: He was made governor of Gaul. 45 BC: He was made Praetor. 44 BC: Murdered Caesar with other liberatores; went to Athens and then to Crete. 42 BC: Battle with Marcus Antonius’s forces. This was the noblest Roman of them all: All the conspirators save only he Did that they did in envy of great Caesar; He only, in a general honest thought And common good to all, made one of them. His life was gentle, and the elements So mix’d in him that Nature might stand up And say to all the world This was a man! William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar , Act 5, Scene 5 (Mark Antony). The phrase Sic semper tyrannis! Thus, ever (or always), to tyrants! Is attributed to Brutus at Caesar’s assassination. The phrase is also the official motto of the Commonwealth of Virginia. John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of Abraham Lincoln, claimed to be inspired by Brutus. Booth’s father, Junius Brutus Booth, was named for Brutus, and Booth (as Marcus Antonius) and his brother (as Brutus) had performed in a production of Julius Caesar in New York just six months before the assassination. On the night of the assassination, Booth is alleged to have shouted “Sic semper tyrannis” while leaping to the stage of Ford’s Theater. And why; For doing what Brutus was honored for… Booth was also known to be greatly attracted to Caesar himself, having played both Brutus and Caesar upon various stages. The well-known phrase Et tu, Brute? Is famous as Caesar’s utterance in the play Julius Caesar, although it is not his last words, and the sources describing Caesar’s death disagree about what his last words were. In Dante’s Inferno , Brutus is one of three people deemed sinful enough to be chewed in one of the three mouths of Satan, in the very center of Hell, for all eternity. The other two are Cassius, who was Brutus’s fellow conspirator and Judas Iscariot (Canto XXXIV). Dante condemned these three in the afterlife for being Treacherous Against Their Masters and enemies of the King/Emperor. Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar depicts Caesar’s assassination by Brutus and his accomplices, and the murderers’ subsequent downfall. In the final scene, Marcus Antonius describes Brutus as “the noblest Roman of them all”, for he was the only conspirator who acted for the good of Rome. In the Masters of Rome novels of Colleen McCullough, Brutus is portrayed as a timid intellectual who hates Caesar for personal reasons, foremost of them the fact that his marriage arrangement with Caesar’s daughter, Julia, whom Brutus deeply loved, was dissolved in Caesar’s political gamble to give his daughter’s hand to Pompey to cement with him an alliance. Cassius and Trebonius use him as a figurehead because of his family connections, and his descendence from the founder of the Republic. He appears in Fortune’s Favourites , Caesar’s Women , Caesar and The October Horse. Ides of March is an epistolatory novel by Thornton Wilder dealing with characters and events leading to, and culminating in, the assassination of Julius Caesar. In the TV series Rome , Brutus, portrayed by Tobias Menzies, is depicted as a young man torn between what he believes is right, and his loyalty and love of a man who has been like a father to him. In the series, his personality and motives are accurate but Brutus’ relationship to Cassius and Cato is not mentioned, and his three sisters and wife Porcia are omitted from the series completely. Brutus is an occasional supporting character in Asterix comics, most notably Asterix and Son in which he is the main antagonist. The character appears in the live Asterix film adaptations – though briefly in the first two – Asterix and Obelix vs Caesar (played by Didier Cauchy) and Asterix at the Olympic Games. In the latter film, he is portrayed as a comical villain by Belgian actor Benoît Poelvoorde: he is a central character to the film, even though he was not depicted in the original Asterix at the Olympic Games comic book. Following sources cited in Plutarch, he is implied in that film to be Julius Caesar’s biological son. The Hives’ song “B is for Brutus” contains titular and lyrical references to Junius Brutus. The Roman Republic was the phase of the ancient Roman civilization characterized by a republican form of government. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, c. 509 BC, and lasted over 450 years until its subversion, through a series of civil wars, into the Principate form of government and the Imperial period. The Roman Republic was governed by a complex constitution, which centered on the principles of a separation of powers and checks and balances. The evolution of the constitution was heavily influenced by the struggle between the aristocracy (the patricians), and other talented Romans who were not from famous families, the plebeians. Early in its history, the republic was controlled by an aristocracy of individuals who could trace their ancestry back to the early history of the kingdom. Over time, the laws that allowed these individuals to dominate the government were repealed, and the result was the emergence of a new aristocracy which depended on the structure of society, rather than the law, to maintain its dominance. During the first two centuries, the Republic saw its territory expand from central Italy to the entire Mediterranean world. In the next century, Rome grew to dominate North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, Greece, and what is now southern France. During the last two centuries of the Roman Republic, it grew to dominate the rest of modern France, as well as much of the east. At this point, the republican political machinery was replaced with imperialism. The precise event which signaled the end of the Roman Republic and the transition into the Roman Empire is a matter of interpretation. Towards the end of the period a selection of Roman leaders came to so dominate the political arena that they exceeded the limitations of the Republic as a matter of course. Historians have variously proposed the appointment of Julius Caesar as perpetual dictator in 44 BC, the defeat of Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, and the Roman Senate’s grant of extraordinary powers to Octavian (Augustus) under the first settlement in 27 BC, as candidates for the defining pivotal event ending the Republic. Many of Rome’s legal and legislative structures can still be observed throughout Europe and the rest of the world by modern nation state and international organizations. The Romans’ Latin language has influenced grammar and vocabulary across parts of Europe and the world. This coin comes with a Certificate of Authenticity. You will be very happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing. Additionally, the coin is inside it’s own protective coin flip (holder), with a 2×2 inch description of the coin matching the individual number on the COA. The item “Brutus Julius Caesar Roman Assassin 44BC Ancient Greek GOLD Coin NGC MS i66641″ is in sale since Friday, July 12, 2019. This item is in the category “Coins & Paper Money\Coins\ Ancient\Greek (450 BC-100 AD)”. The seller is “v8m4i09oh” and is located in Midlothian, Virginia. This item can be shipped to United States.

- Coin Type: Ancient

- Certification Number: 3927929-046

- Certification: NGC

- Grade: MS

- Composition: Gold

- Culture: Greek